THE BEGINNINGS OF PHILIPPE TOURNAIRE

Les débuts de philippe tournaire

Self-taught, I groped my way around for a long time, using the knowledge I'd picked up from my family and on my travels. In Morocco, for example, I met craftsmen who worked with very rudimentary tools.

A cellar to learn the ropes

Lorsque j’ai commencé l’apprentissage de radio-électricien, je faisais déjà des bijoux, des vêtements, du tissage et même des chaussures depuis longtemps. Mes parents, plutôt modestes, m’avaient transmis que quand on voulait quelque chose, il fallait se débrouiller pour le faire. Le système D nous a été transmis très tôt à mes frères et à moi-même. Si j’aimais quelque chose, je ne me posais pas la question d’aller l’acheter, mais je me demandais comment je pouvais le réaliser. Le musée de l’Homme à Paris m’a donné des pistes de réflexion afin de répondre au récurrent «Pourquoi ?». Situé au Trocadéro, ce musée met en avant la diversité de l’humanité dans les domaines anthropologique, historique et culturel. Ce qui m’attire ici, ce sont les objets du quotidien de toutes les civilisations ayant plus ou moins disparu. Ma fascination pour ce patrimoine me poussait à chercher et à reproduire comment les premiers hommes façonnaient leurs objets et pourquoi d’utilitaires ils sont devenus aujourd’hui des œuvres d’art.

I really liked jewelry. As a radio electrician in the countryside,

il faut être très polyvalent, aussi j’installais des machines et je travaillais le cuivre. J’ai eu la chance d’avoir appris à bricoler avec des grands-parents menuisiers-ébénistes d’un côté et agriculteurs de l’autre, cela m’a aussi beaucoup aidé. Ces métiers très variés qui demandent de l’ingéniosité et du savoir-faire m’ont permis de pouvoir réaliser tout ce que je voulais. Par exemple mon grand-père menuisier avait sa forge sur laquelle il fabriquait ses outils. Cette facilité apparente et ce savoir-faire de mon grand-père auprès duquel j’ai passé des heures à l’atelier, m’ont ouvert tout droit la porte du travail artisanal et les clés pour comprendre son long processus.

I was also lucky enough to realize very quickly that by concentrating on small objects, my asthma bothered me less, and I forgot that I had to breathe. Asthma is both psychological and pathological. Art therapy didn't exist, but I'd found something that soothed me and did me good, in addition to sport. Listening to my body, concentrating and making art objects were the key, the trigger...

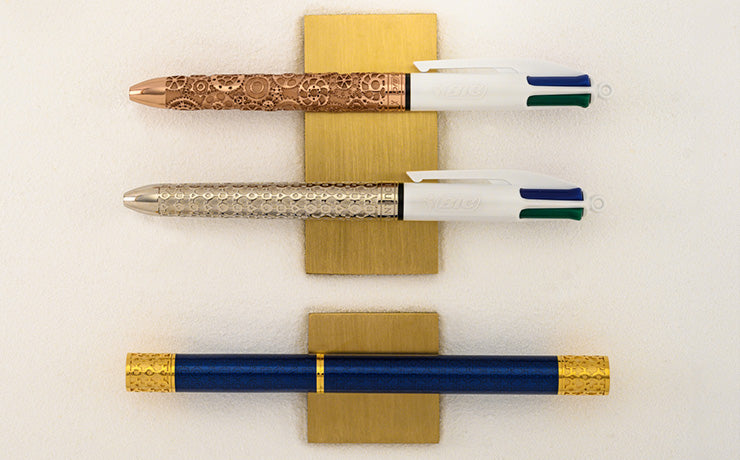

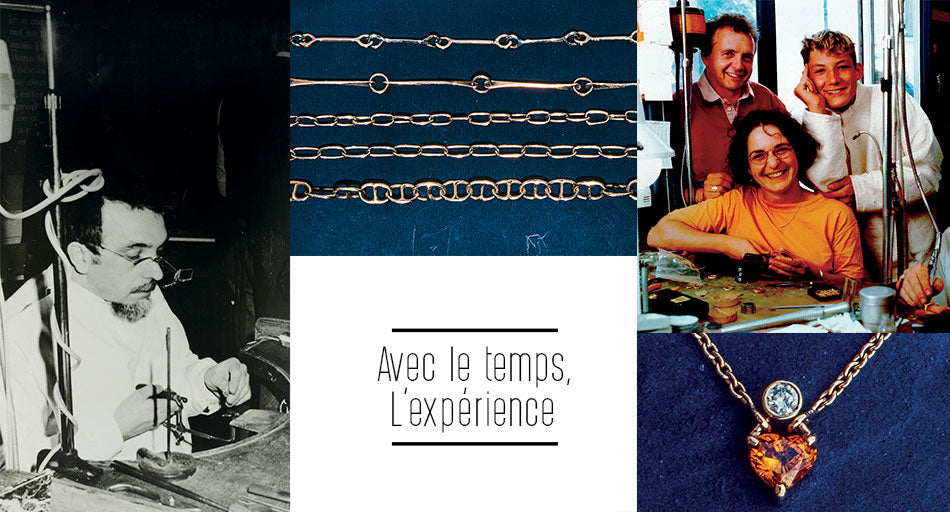

After 20 years of living as a family in what was at once a home, workshop and store, we moved in 1971 to Baffie, a hamlet 1 kilometer from Saint-Germain-Laval. My parents had restored a very old, semi-buried house. The cellar overlooked, and still overlooks, a path that leads to the famous Baffie bridge and its chapel. At the age of 22, I seized the opportunity to set up a workshop there. As I couldn't stand upright, I dug out 20 centimetres of the floor and raised the door. Once the walls and floor were clean, I set up my workbench, rudimentary tools and an interior display case to showcase my first creations. I also set up a makeshift bedroom in a corner, as I often worked late into the night... I lived there for 7 years, in a kind of autarky, working slowly and long on my creations. Completely untrained in any technique, I tried out everything I could think of, using any metal or object that might inspire me. Little did I know, then, that this work was an essential gestation period for the birth of my style, and that two reasons prompted me to start working only in the mornings when electricity was on. My passion for jewelry, which I was always making for friends, and the arrival of the first integrated circuits. From one day to the next, we had to work on machines we didn't know how to operate. At the beginning, when we had to repair a lamp or a transistor, there was an intuitive side to it, you had to understand how it worked, it was like a treasure hunt for me. When integrated circuits came along, we just became parts changers. We had to measure the voltage and if it didn't match the specifications, we had to change the integrated circuit, but we had no idea why. Working like that didn't interest me at all, there was no longer the challenge aspect, finding a fault was a bit of a game. I knew then that the profession would continue to evolve in this direction, and that it would lose all its interest in my eyes. Besides, I needed to find time to respond to my ever-growing creative urge.

"I never thought jewelry could become a profession".

Une année durant, j’ai « tarabusté » le responsable des impôts à Roanne pour qu’il m'autorisât à faire des bijoux sous un statut spécial. Ce qui correspond actuellement à l’auto-entreprenariat ou la micro-entreprise n’existait pas, on devenait tout de suite entrepreneur. La TVA sur les produits de luxe était de 33 % et si je me lançais sans statut, cela n'aurait pas été possible. J’ai donc étudié la législation avec un ami, puis un beau jour la solution s'imposa : je me baptiserais «sculpteur sur métaux précieux». Je retournais voir le gars des impôts à Roanne, monsieur Lopez. Les noms de ceux qui vous aident à avancer restent. Puis, en mars 1973 lors d’un dernier rendez-vous, il me dit :« Bon, votre histoire ça ne va pas se jouer sur des millions, je vous accorde ce statut ». La demande croissante dépassait le cadre amical et je devais pratiquer légalement. J’ai donc obtenu mon 1er poinçon de Maître et l’autorisation d’acheter et de revendre des métaux précieux avec un livre de police. J’avais mis deux ans, en allant voir ce monsieur Lopez régulièrement pour trouver la solution. En tant qu’artiste je n’étais pas soumis à la TVA, j’avais moins de contraintes et d’administratif qu’un entrepreneur. Et à partir de là, je me suis engouffré à fond avec ce statut pendant 11 ans.Lorsque j’ai commencé officiellement, je ne connaissais pas du tout le monde de la joaillerie et des pierres fines. J’ai été aidé par des gens qui m’ont donné les bases pour faire du bon travail. Dès 1973, j’ai côtoyé régulièrement un tailleur de pierres lyonnais qui s’appelait Jacques Secretan. J’allais le voir pour avoir des réponses à toutes les questions que j’avais sur les pierres. Même si elles étaient parfois bizarres, il tâchait de répondre. Cet homme a été une personne très importante dans mon apprentissage de la joaillerie car il m’a permis de comprendre la gemmologie et de me forger ma propre vision des pierres.

A diamond dealer on rue Mercière, Jean Grosfilley, also took the time to teach me about this exceptional stone. Above all, there was another person who was very influential in my early years. A jeweller, Meilleur Ouvrier de France, by the name of Jean Giraud, whom I met at the Saint-Étienne Fair when he was working in public. He had a store in Saint-Chamond and was the first person in the trade to encourage me. He invited me to visit him in his workshop, which was a great vote of confidence. It took me 3 years before I dared to go...

All these people, encounters, persistence and hours spent at the workbench have taught me how to work. It gave me the opportunity to build an identity, a style that is reflected in my creations.

In the beginning, I was in the country, I had no expenses, I wasn't married and I didn't have any children yet. I pursued "my bohemia", then word-of-mouth brought me more and more customers who kept me working and living. I continued working part-time as a radio electrician with my father until 1976, after which I devoted myself entirely to jewelry. I also set about building a small house above Baffie with my own hands. I lived there from 1978, the year Romain, my first son, was born.

I have very fond memories of my cellar, where I learned a lot, and not just about my job. Radio fed my mind and my curiosity. While I was working, I listened to Jacques Chancel on his " Radio-scopie " program, where he always invited fascinating people who encouraged me to read their books. But I also listened to France-Culture, where science and history were very present. In the end, I learned more by listening than by reading or going to school. I had no training whatsoever, and it was my great good fortune not to know how jewelry was made. I just did what I felt like doing.

C’est une contrainte au début, car en ne sachant pas faire, on met plus de temps à fabriquer. Mais j’ai pu réinventer les techniques existantes à ma façon et créer mon propre savoir-faire. Et dans la mesure où j’avais une très bonne connaissance de la menuiserie, de la forge et de l’électronique, ces savoirs se sont connectés et j’ai trouvé des solutions alternatives. De cet inconvénient devenu contrainte, en réalité sont nés mon style et mon talent.

In 1979, the price of gold rose from 4,000 to 15,000 euros per kilo in the space of a month or two, when the USSR entered Afghanistan. From one day to the next, the threefold increase in my raw material costs put a huge brake on my business. At the same time, to earn a little money to finance my materials, I had a friend who dreamed of opening a nightclub. He had helped me fit out the cellar, so I gave him a hand.

In 1981, the year Mathieu was born, the project came to fruition and the " Vers de Gris " opened its doors. It was in the evening, so I could earn a bit of money bartending and DJing. I met people who had dynamic businesses in the area. Their success gave me confidence, and the idea was born that I too could set up in the city.

The guarantee of uncompromising craftsmanship

Our titles and labels

Made in France

Made in our workshop

100% secure payment

3x free of charge possible

Free delivery & returns

100% secure and free

Jewellery committed

Ethical and responsible jewelry